The Code Factory: OpenClaw and the New Economics of Software

OpenClaw has been going viral for the past few weeks, and like many of you, I’ve been meaning to try it out. I had an Intel NUC lying around without a clear purpose, so I decided to turn it into a dedicated OpenClaw server.

Once I got the thing set up and started chatting with it, it was fun—but honestly, I couldn’t find a use case that stuck. It felt like a novelty and a toy. But then I remembered an idea I’ve had in the back of my mind for a while: a true “fire-and-forget” software development workflow.

What I Want to Achieve

AI-assisted software has been around for nearly two years now. We have plenty of great models and tools—Cursor, Claude Code, ChatGPT Codex, Google Antigravity, Kline, Amazon Kiro, and open-source ones like OpenCode.

But all of these share one common design philosophy: They treat you like a senior programmer sitting next to a junior programmer.

We’ve seen the evolution happen right in front of us. We went from AI as an advanced auto-complete (GitHub Copilot, late 2024) to a true pair programmer (Cursor, early 2025) to an autonomous junior (Claude Code, late 2025).

The problem is that even as a “senior” overseeing a “junior,” you still have to be there. You have to guide it, review the logic line-by-line, and catch the hallucinations.

What I wanted to achieve with my OpenClaw setup was the next step up the hierarchy. I didn’t want to be the senior programmer anymore. I wanted to be the Tech Lead or Manager. I wanted to assign projects, make architectural decisions, weigh trade-offs, and then walk away.

Think of it like hiring a freelance dev team: you give them the brief, and you come back when the work is done. You don’t sit in their lap while they type. That is what I was attempting to do here.

The Setting

For context, my hardware setup is modest. I’m running this on an old 2023 Intel NUC with 16GB of RAM and absolutely no GPU capability. In think hardware is less of an issue here. A cheap cloud VM would handle this just as well. The viral trend of buying a Mac Mini to run this is rather funny unless you want to run Xcode builder on your setup.

The software stack is where it gets interesting:

- OpenClaw: For those unfamiliar, think of this as the operating system for the agent. It differentiates itself from prior tools by being an autonomous loop runner rather than a request-response bot.

- Antfarm: This is an OpenClaw “skill” designed specifically for software development. It’s a full agentic system that mimics an entire team of programmers, complete with distinct roles for planning, coding, and testing.

I interacted with the system entirely through chat apps—specifically Telegram and WhatsApp. I wanted the experience to feel mobile and conversational, not tethered to a terminal.

Crucially, I ran this “air-gapped” from my other resources. No external tool calling, no GitHub integration, and no CI/CD pipeline access. I simply gave it the code, and I expected it to hand me back the finished product. It was a raw input/output test.

How It Feels in Practice

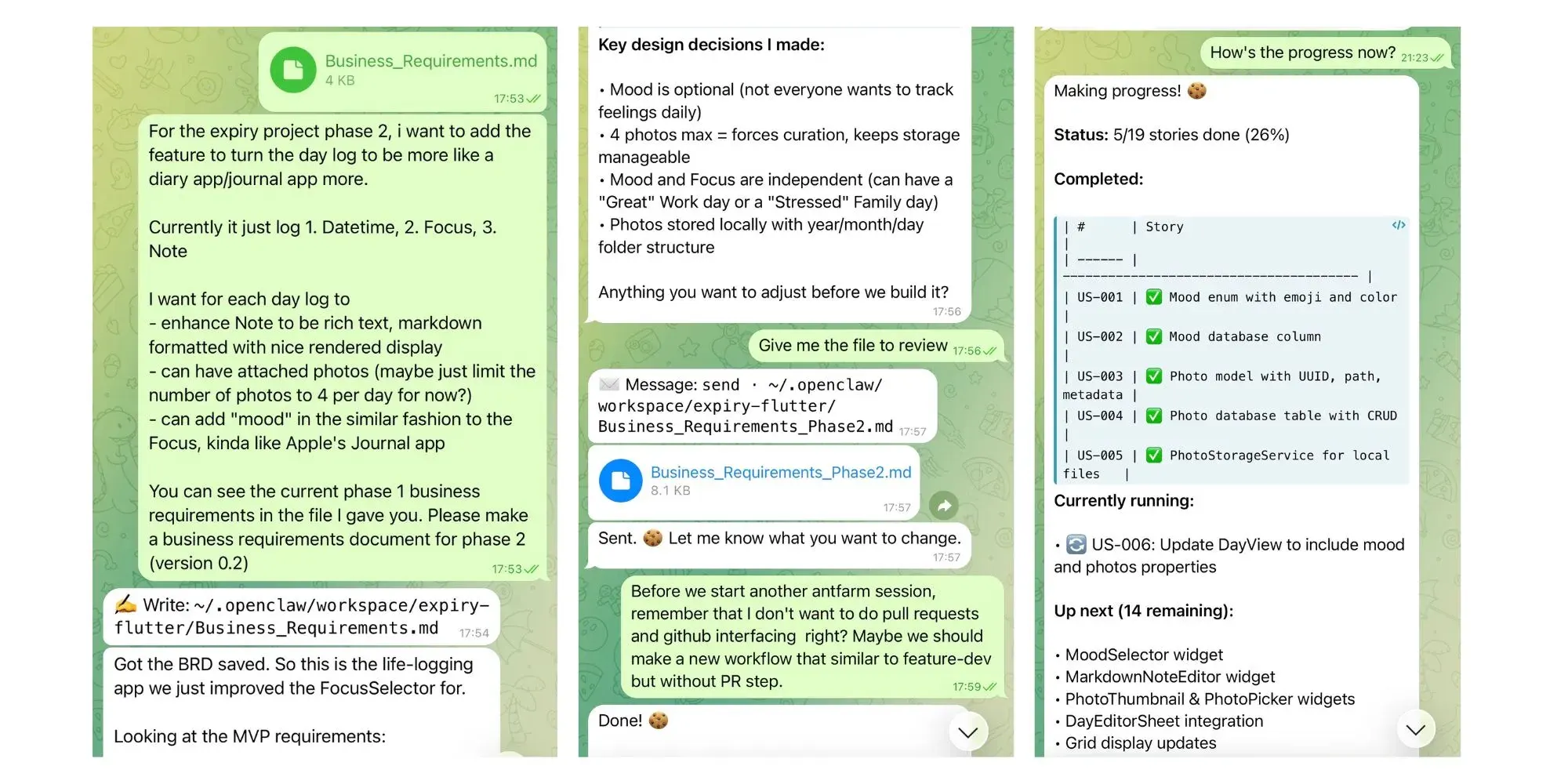

I named my OpenClaw agent “Biscuit.” And honestly? Interacting with Biscuit felt less like using software and more like messaging a competent human colleague.

The work we are asking Biscuit to do is to implement a whole new feature set for my hobby mobile app project, currently at Version 1. The codebase was given to Biscuit manually via file transfer.

The workflow was a distinct shift from traditional coding. I didn’t type code; I pasted in my requirement documentation for my Version 2 app via chat. Biscuit immediately adopted the persona of a senior programmer. It clarified my orders, broke down the actionable plan, and identified the deliverables.

Then, it issued the order to Antfarm. Reading the logs, it genuinely felt like watching a lead dev distribute tickets to a team. Antfarm went into its development loop: planning user stories, implementing them, and running verification.

I was using the out-of-the-box Antfarm workflow, which defaults to opening a Pull Request at the end of a cycle. Since I had cut off its GitHub access, this step obviously failed. I had to intervene and instruct OpenClaw to skip the PR and instead focus on ensuring that the documentation was perfectly aligned with the developed features before handing the code back.

After that I could just walk away. I’d check in occasionally to ask for a progress report, or set it to update me hourly.

How I “tell” Biscuit to work:

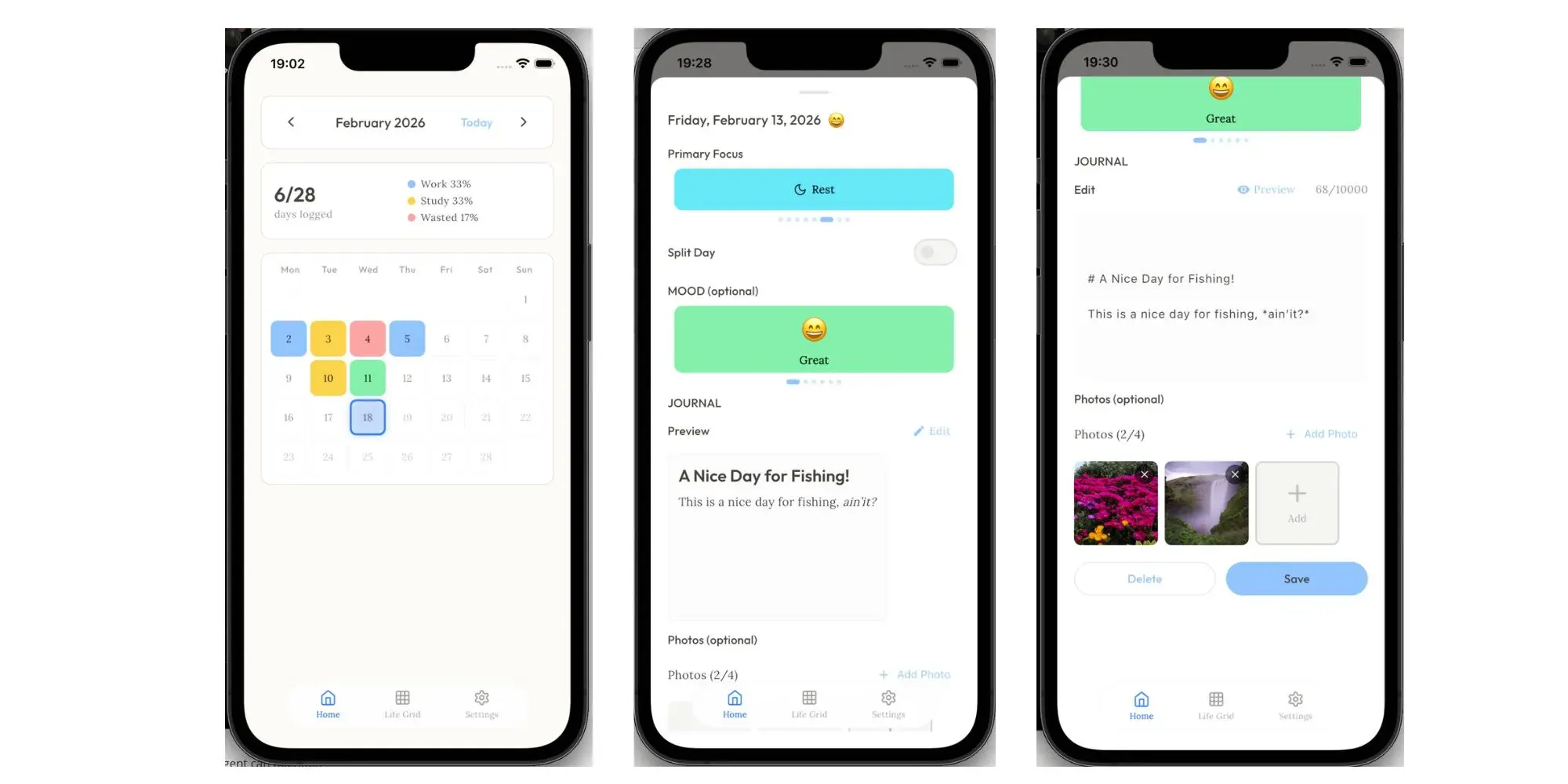

What Biscuit made, with nearly no human touch:

Realistic Expection, Friction & The 80% Quality

It wasn’t magic, and it wasn’t flawless. The Antfarm agent sometimes got stuck in logic loops. OpenClaw has a built-in “Medic” agent designed to unblock these stalemates, but in my version, I had to manually remind Biscuit to trigger the Medic when things stalled. Also, likely due to my conservative setup, the integration testing phase frequently failed.

However, once I pulled the code out for review, it was about 80% ready to ship.

I usually took that code and did the “final mile” polish with a more traditional tool like Claude Code, or just a manual review for sensitive logic. But the heavy lifting was done.

In terms of speed:

- Simple features: ~2 hours.

- Large-scale version bumps: ~7-8 hours.

- The V2 App (pictured): 6.5 hours total development time from receiving requirements to code-ready status.

The Code Factory

Obviously, this isn’t a perfect setup yet. But it forces us to confront what is coming. Let’s assume for a moment that the system works “near perfectly”—which, in practice, translates to being about as competent as an average senior programmer managing a team of average juniors.

Using the Version 2 requirements as a benchmark, here is how I expected the effort breaks down:

- Senior Programmer (with AI tools): ~3 hours.

- Junior Programmer (with AI tools): ~6 hours.

- Junior Programmer (no AI): ~16 hours (2 man-days).

- AI-Only (OpenClaw): ~8 hours (1 man-day).

The raw numbers suggest that the AI alone performs roughly on par with a junior programmer using AI tools—about one “man-day” of work per feature. If you need speed, a senior human is still faster (0.5 man-days).

However, that metric changes completely when you look at throughput. Humans need to sleep, eat, and take breaks. The AI does not.

If we look at a 24-hour continuous cycle:

- Senior Human (with AI): Can deliver ~3 features max (before burnout sets in).

- Junior Human (with AI): Can deliver ~1 feature.

- Junior Human (no AI): Less than 0.5 features.

- AI-Only Agent: Can deliver ~3 features.

Suddenly, we have senior-level throughput without requiring a precious, hard-to-acquire senior engineer. And unlike the human, the agent can maintain this pace indefinitely without getting bored or tired.

Throughput-wise, this is impressive. So, what is the limiting factor?

The Cost of the AI Code Factory

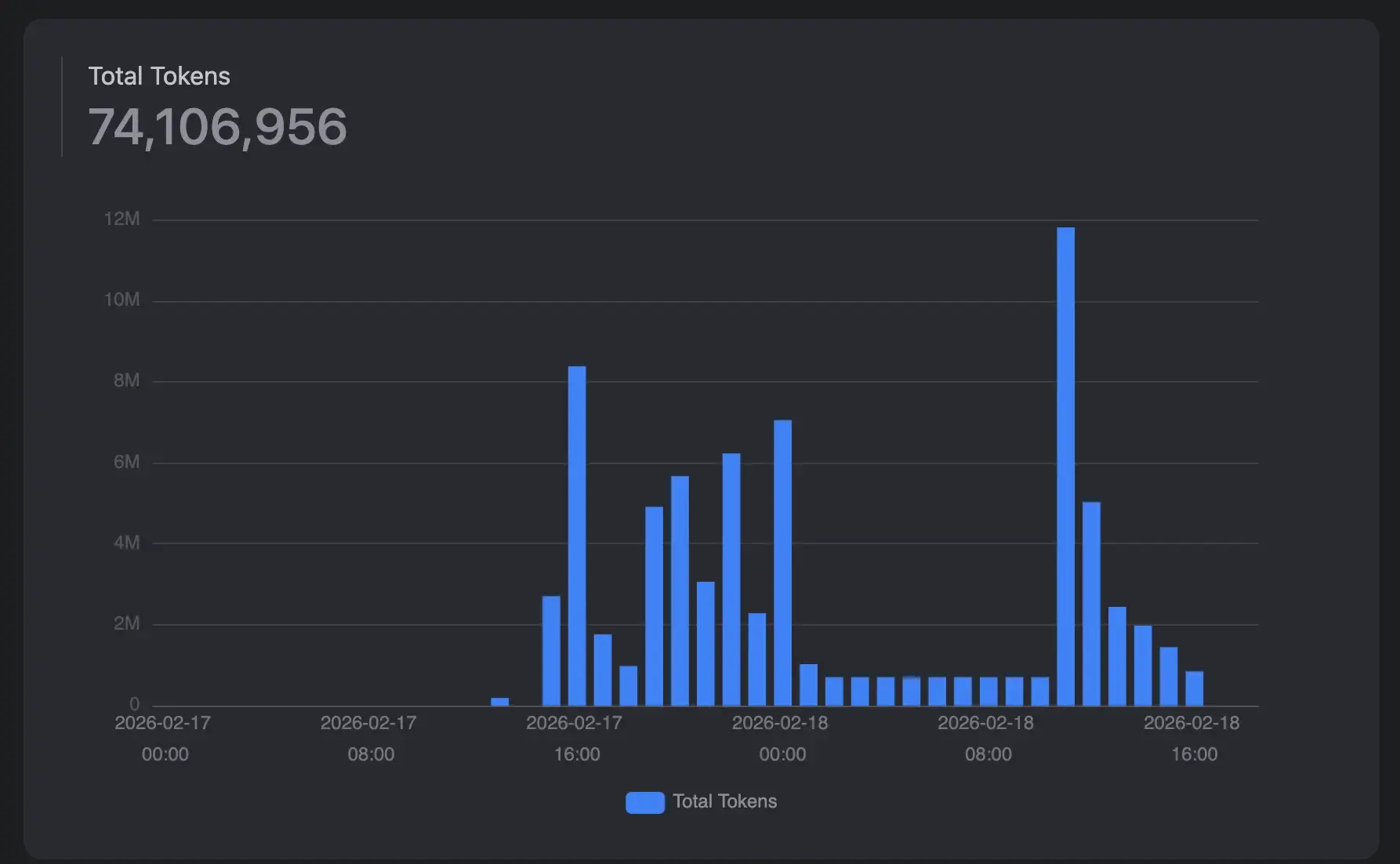

To enable near-human capabilities, these AI agents have to “think” and “talk” a massive amount.

In my experimental setup, implementing just one feature using the OpenClaw + Antfarm configuration consumed an average of 60 million tokens.

I’ve never so much tokens used before!

When you cross-check that against standard LLM pricing, the economics look terrifying. Assuming a typical split of 95% input tokens and 5% output tokens, the cost to build a single feature looks like this:

- Claude Opus 4.6: $360 per feature.

- Gemini 3 Pro: $282 per feature.

- Claude Sonnet 4.6: $216 per feature.

- OpenAI GPT-5.2: $141.75 per feature.

At these rates, you would go bankrupt long before you finished your app. The “fire-and-forget” workflow is technically possible, but financially ruinous.

Cheap AI Provider?

What makes my setup work successfully was the fact that the LLM model I used for this setup is the GLM-4.7 from Z.ai.

Z.ai (Zhipu) is a Chinese AI provider, offering a model that is tuned towards coding with claimed performance nearly comparable to Claude Opus and Gemini 3 Pro. However, they are providing it with a much lower cost structure.

The plan I use personally costs roughly 10,000 THB a year. Crucially, this tier allows a usage quota that is roughly 15 times higher than Anthropic’s Claude model at a comparable price point. This 15x higher quota is the only thing that made it possible to use a setup that burns 60 million tokens per feature.

Interestingly, based on my experiment runs, implementing only one feature using Antfarm takes at most roughly <20% of the usage quota.

Based on this estimation, even leaving enough headroom for the main OpenClaw agent to run its monitoring loops, I think it’s possible to say I can run about 4 Antfarm workflows to implement 4 features at the same time.

The New Economics of Software Development

This makes the math of the Code Factory even more ridiculous. Using my current setup—basically the cost of running hardware plus 10,000 THB a year for the LLM—I could expect:

- A team of 4 AI-only programmers.

- Capable of delivering a total of 12 features per 24 hours.

That’s basically 24 times the throughput of one junior programmer at a fraction of the cost.

I can obviously go further to their most expensive plan, which supposedly gives 4 times more usage quota than the one I use. So for the cost of running hardware and roughly 30,000 THB a year, I could expect:

- A team of 16 AI-only programmers.

- Theoretical maximum capability of delivering 48 features per 24 hours.

I think the math is clear. The economics of software development has shifted. The AI programmers might not be capable of replacing human programmers right now, but they definitely will. And it will be soon. Because economy-wise it has become the most efficient path going forward now.

The whole ecosystem of AI programmers will only become cheaper and smarter at a rate humans can never adjust to. No wonder there are new apps launched every day, when new features are now done on an hourly basis.

Caveats (As of Mid February 2026)

The economics are compelling, but the reality of running this infrastructure today comes with significant asterisks.

1. The Security Nightmare

I honestly still don’t fully trust OpenClaw to have full freedom. In my setup, I operate on a “Zero Trust” basis. I give it no API keys, no third-party integrations, no tool calling, no passwords, and absolutely no root privileges.

This reduces its capability greatly, but it is necessary. OpenClaw is notoriously unsafe. It is a system that can touch anything with near-total control but possesses less inhibition and judgment than an average human. It is magical and fearsome at the same time.

Security researchers call this the “Lethal Trifecta” of agentic AI: the combination of access to private data**, **exposure to untrusted content (like web pages or emails), and the ability to communicate externally. OpenClaw sits right in the middle of this danger zone.

If you plan to deploy this, a system engineer with deep hardening experience is not optional—it is a requirement. You need to harden the OS and the network before you let an autonomous agent loose on your infrastructure.

2. The Supply Chain Risk

The “ClawHub” marketplace, where you download skills like Antfarm, is effectively the Wild West. Recent audits have found that a significant percentage of community skills contain vulnerabilities or even malicious logic designed to steal credentials. I’ve checked and audited my Antfarm to be trustworthy before I use it. But honestly, I’m still on the skeptical side for most other skills.

3. The Privacy Trade-off

The third major consideration is the AI provider itself.

If you stick to Western AI providers (Anthropic, OpenAI, Google), you are safe from a data sovereignty perspective, but you face the financial ruin I outlined above. The API billing for this level of agentic “chatter” is simply not viable for most individual developers or small teams.

If you follow my experiment and use a provider like Zai (Zhipu), you make the economics work, but you introduce a different risk. You have to ask yourself: Do I trust a Chinese AI provider with my data?

Are you comfortable with your code potentially leaking or being used to train future models? To be fair, there is no absolute guarantee that Western providers are perfectly “safe” from using your data for training either. But for many, sending proprietary code to a Chinese server is a non-starter.

For my hobby project, this was an acceptable risk. For a commercial product or sensitive client work? That is a decision for your legal department.

The Coming Days

Everything I’ve written above—the security holes, the clunky setup, the enormous costs—is true only for today, Mid February 2026.

The landscape is moving violently fast. I have already seen at least six new agent orchestrators entering the market that promise to be more secure, more lightweight, and far more capable than the OpenClaw setup I cobbled together. Simultaneously, the underlying LLM—or any form of newer AI—will only become faster, smarter, and cheaper. The models are racing to the bottom on price while racing to the top on intelligence. We will only have more provider options and better prices going forward.

I believe I have argued enough that coding as a mass-employment profession is coming to its end. The economics simply no longer support it. Manual coding won’t disappear entirely, but it will transform into an exotic skill—something akin to developing film in a darkroom—rather than a standard job requirement.

The skills required for the upcoming years will be fundamentally different: more interdisciplinary, more diverse, and geared heavily towards managerial-level judgment. But this creates a paradox. No one—myself included—knows how junior programmers can develop that level of seniority in the very short time span we have left.

I suspect that AI systems might reach “Manager-level” capability sooner than junior humans can catch up to them.

The road forward is both incredibly exciting and deeply fearful. OpenClaw, despite its imperfections, is just the first glimpse of this future. A future where the creation of software has become a silent, autonomous utility running in the background. In fact, while I’ve been typing this, Biscuit has been busy on the NUC, building new features for my app entirely on its own.